Infinite Seeker

KoreAm Column / November 11, 2013

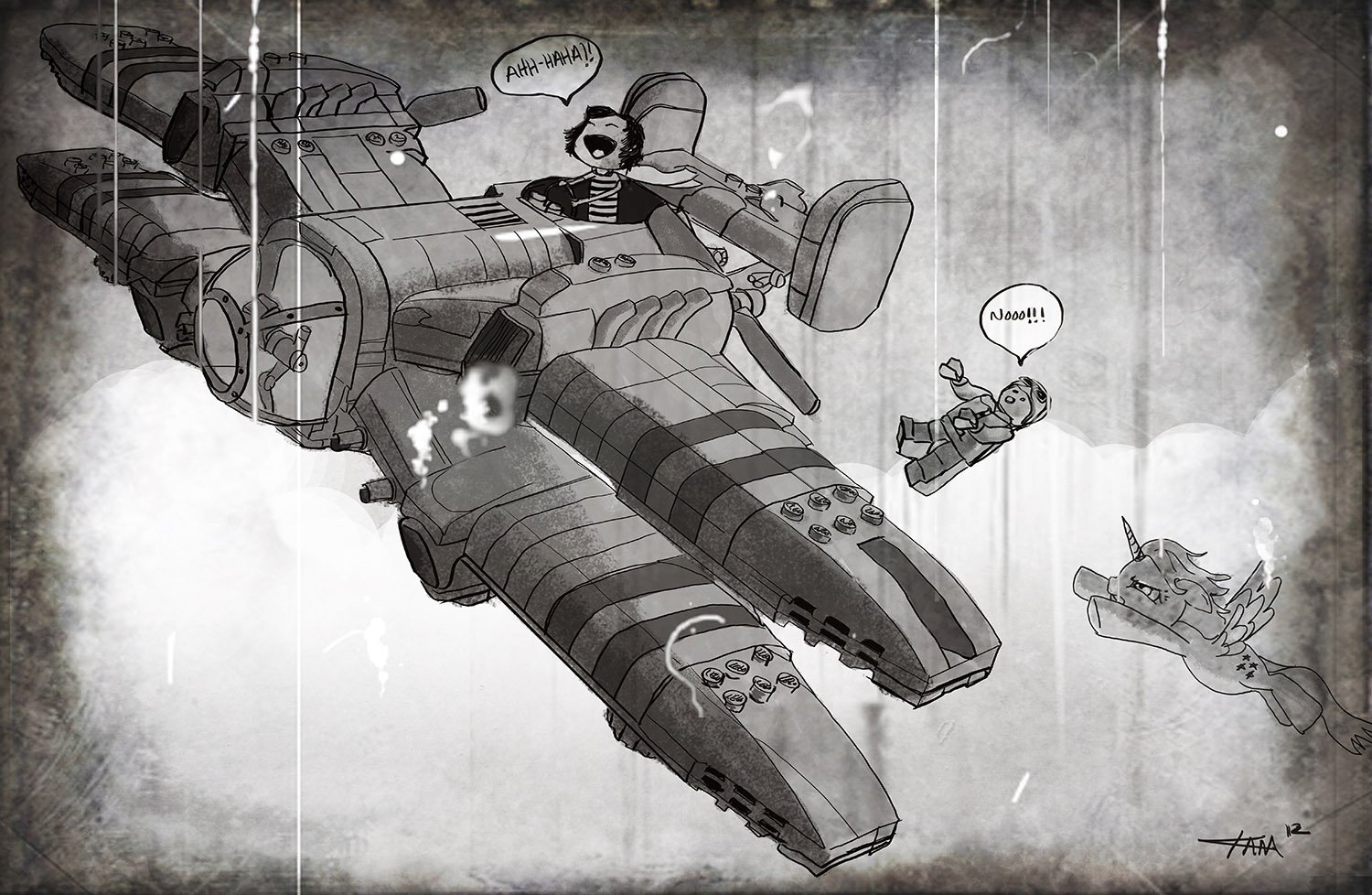

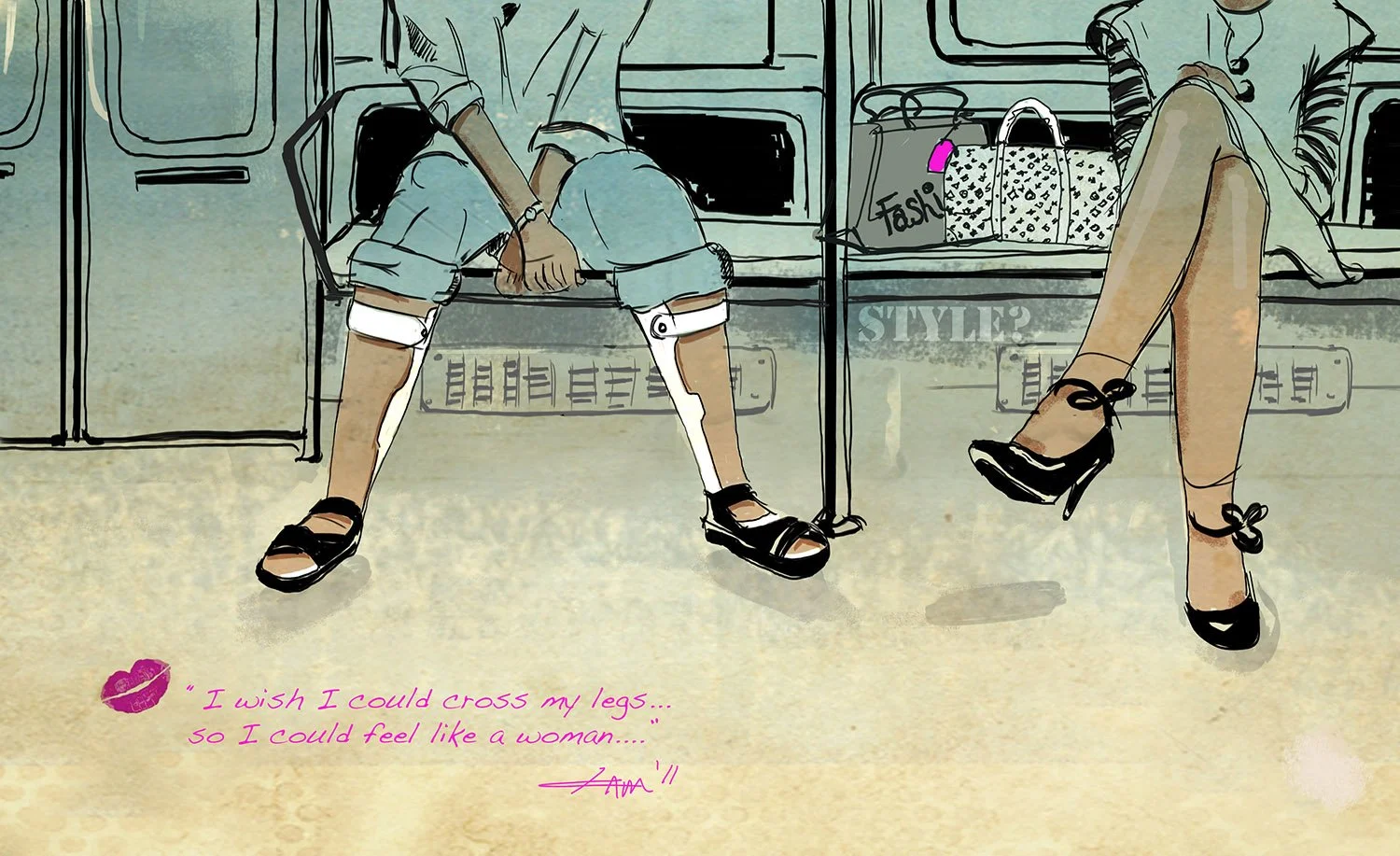

While looking at the Detroit skyline from my tiny studio apartment, I made the impetuous decision to visit Korea. This would be my first time back in 20 years, since my adoption at age 4 by a white family in Michigan. It was the summer of 2003, and I booked my ticket two weeks before departure. This was also the period when the mysterious weakening of my legs had begun (the first signs of my genetic neuromuscular disorder that made me a full-time wheelchair user), and this hastened my sense of urgency, despite feeling nervous about traveling alone.

Fortunately, once I got to Korea, I wouldn’t be alone. A group of devoted classmates from my design college, which had a large number of international students from Korea, had offered to host me that summer and show me around my lost country. Back in college, I began inadvertently making friends who looked like me, and consequently tossed into “Korean life.” As someone who grew up in a predominantly white community, including my own parents and siblings, this sudden surge of similarity made me curious, and I jumped in with both feet—from learning all about Korean cuisine to Korean dramas and even going as far as teaching myself Hangul (the Korean alphabet), just so that I could read and memorize popular Korean songs to surprise my friends during karaoke outings.

I went from having all white childhood friends to mostly Korean friends, and thus began my education about my heritage, of which I knew nothing about. Or so I thought. As the plane touched down at Incheon Airport, I felt excitement. And as soon as my wobbly feet touched Korean soil, I felt at home.

For the next couple of weeks, my friends took turns showing me around. I met their families and lived as they did. Their families were nurturing hosts, treating me to home-cooked traditional Korean food. As we sat on the floor indulging in the colorful array of stews, meat and banchan (side dishes), I felt kinship and comfort. All of this seemed remarkably familiar, and I realized my memory had escaped me for so many years.

I found myself intently observing the children playing in the streets, as if watching them would extract a sense of what I was like as a child in Korea. But with all the positive moments, I also experienced moments of disconnect. Natives would target me as either not a true Korean or a disgrace because I didn’t speak their language. They could not understand why I didn’t, nor did they care, and would look upon me with pity as they glared down at my cane. When we drove through the bustling Seoul through pouring rain, all I could see were a sea of umbrellas covering the city. At one moment, I remember all the heads lifting up, and I could see a sea of faces that looked like me.

When it was time to leave, I felt sad, as I gazed at my birth country from the airport conveyor belt. Leaving Korea was difficult, and suddenly, Michigan no longer felt like home. I cried.

* * *

The story I know, or remember, of how I came to be begins at age 4. Belonging to a family was not a given for me. It required a long journey across the Pacific Ocean to find them. I am told I was abandoned at birth and my biological mother left, giving no name or trace of who she was. Sporadically, I would think of this alleged moment. I felt like she was a phantom in the delivery room. Was she really there? Did such a person exist?

I was transported from that little birthing clinic in Daegu, South Korea, to a convent. My first week in this world was spent with nuns and other abandoned children. Then I moved to an orphanage where I lived until being adopted by an average-income white couple in their late 30s, who already had three “homemade” sons at home in Michigan.

My very first photograph in the States shows me being greeted by my (adoptive) parents, Sandra and Rodney, at the airport, a picture that is always pinned up on the wall of my home. My mother recalls the story of seeing me being carried from the terminal with my tongue sticking out at everyone. “Oh, boy,” she thought, “this is going to be a ride.” They took me home to meet my three brothers, and I was now theirs.

The combination of newly nervous adoptive parents and the confusion of a little girl who did not know what family meant led to a rocky beginning, and I’m told I tested my parents to the limit. I’m sure they had their own jitters. I was not only adopted, but foreign. I brought my language with me, so communication was initially a challenge and would require my mom “bawking” like a chicken in order to relay the message that chicken was for dinner. For the first couple months, I whimpered for my “eomma” (Korean for “mom”), while crying myself to sleep. When I was 5 years old, I had a friend named Meena, who was also a Korean adoptee. She was the only friend that looked like me. One day I stopped seeing her around, so I asked my mom what happened to her. “She was sent back,” she said. I wondered if I would be sent back, as well. I knew there were problems, and sensing my parents’ anxiety and unstable relationship, I knew I was not the perfect child and further stressed an already crumbling marriage. From a young age, I knew what uncertainty and temporary meant. Nothing was forever in my tiny world.

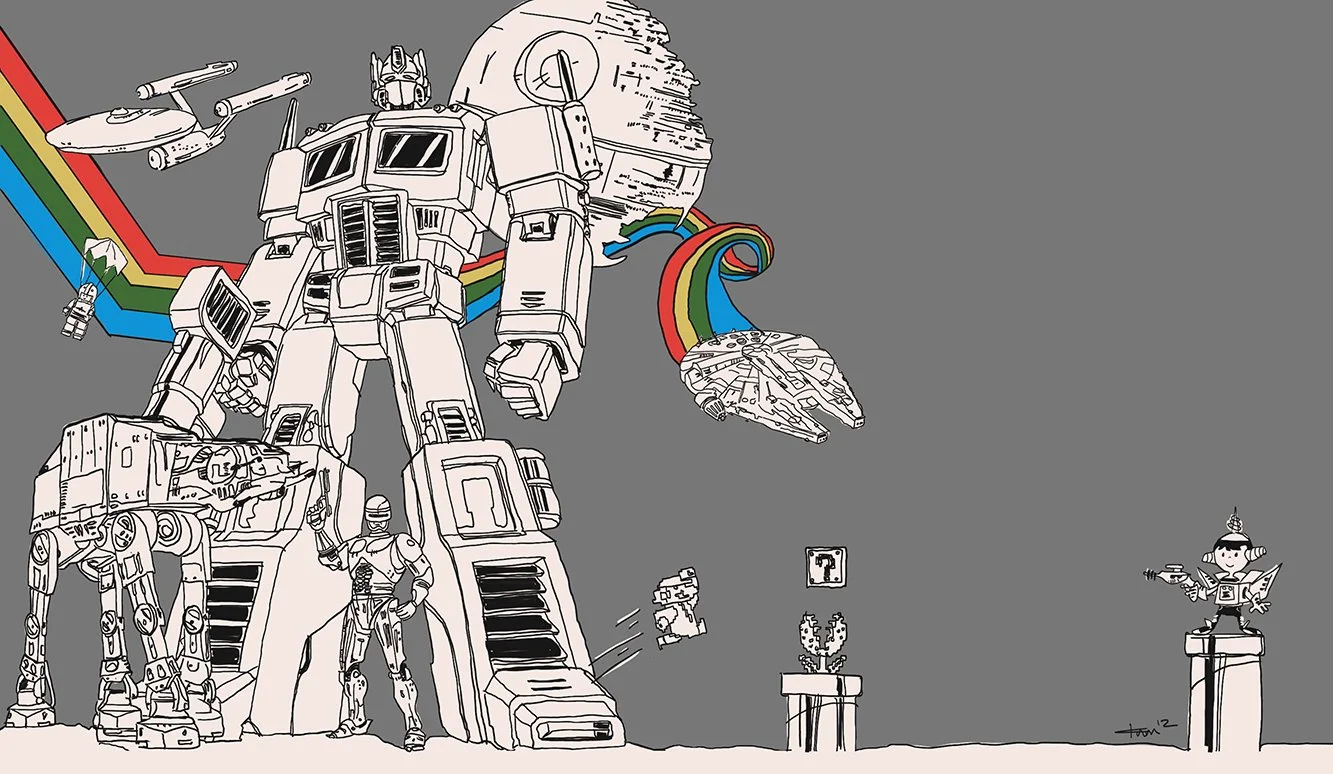

I grew out of the mischievous child to an overly responsible and studious kid. Like everyone, my family had its own turmoil and issues, but I knew that they loved my brothers and me, and gave it their best. My life would become typically suburban. I played sports from childhood through high school and romped around with my three brothers, playing army, neighborhood flashlight tag and video games. I don’t recall feeling too different from others or my siblings.

Soon, I became one of them. Soon, I no longer saw a difference between them and me, and it was my families’ faces and bodies that I detected in my reflection. There must have been a moment I forgot who I was, where I came from, and shifted into the new me. My new surroundings now defined me, and I assimilated in order to survive and thrive.

It wasn’t until sixth grade and through junior year that I would be made aware of how different I really was. Like most children enduring their puberty years, I came under the gaze of critical peers who often made their chinky eyes at me. They capitalized on anything different about me. I was born with a cleft palate, so they would make fun of my voice. To this day, I hate how I sound. The first three months of life, I was told that I was in the hospital due to my cleft palate, chicken pox and measles that left scars on my face, so my classmates called me “crater face.”

As I got older and looked in the mirror, I began realizing how different I was from my white peers and family members. I felt ugly and would feel that way for most of my life. I wanted to be like everyone else, but was picked on for much of junior high. I grew quiet and reserved. I lived inside myself, even at home. I would sometimes spend my lunches in bathroom stalls or in the library. I still had friends, was heavily involved with school activities and made all A’s, but never felt truly connected to any category or group.

It wasn’t until college, when I was exposed to a whole new world, and the thrill of education enveloped me with new thoughts and ideas, that I realized those junior and high school years were so limited and meaningless. It was significant that I had moved away from my family and started forming my own self, diversifying my circle and experiences. I now owned the freedom to explore a self I did not know. I experienced my Korean period. I visited Korea, had Korean friends and became familiar with what my past could have looked like. But after graduating from college and living and working in the “real world” for several years, perhaps not unlike many second-generation Korean Americans, my Korean identity became less central to who I was.

I ended up unintentionally marrying a Korean adoptee, a former college classmate. He is very much like myself—not really Korean, not really Caucasian, just his individual self. We are both well-adjusted about being orphans and adoptees, with the opinion that it does not define who we are.

In 2010, I took my husband to Korea. It was his first time back. We ended up tracing my steps from birth to my orphanage, and I had the great and unexpected honor of meeting my foster mother who remembered me intimately. Though decades had passed, she lovingly recalled memories of what I was like as a child.

I saw my very first baby picture in the courtyard of the convent and was able to play with newly placed orphans in the orphanage where I once played. It was a wonderful experience, but somehow felt different than my 2003 visit. I felt like a tourist this time. I had grown past my Korean phase. I was still proud to be Korean, but felt odd to be completely surrounded by people who looked like me.

* * *

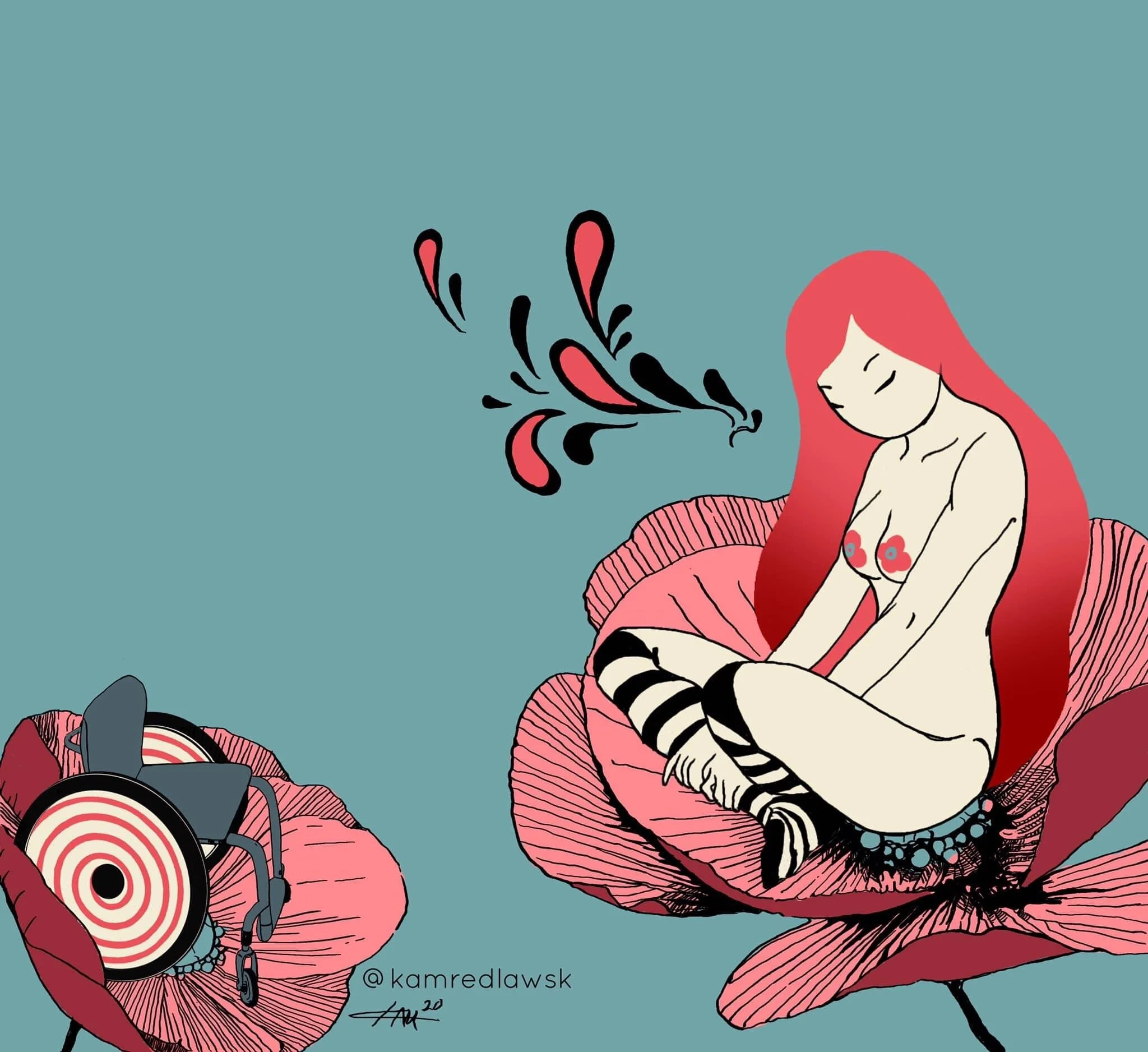

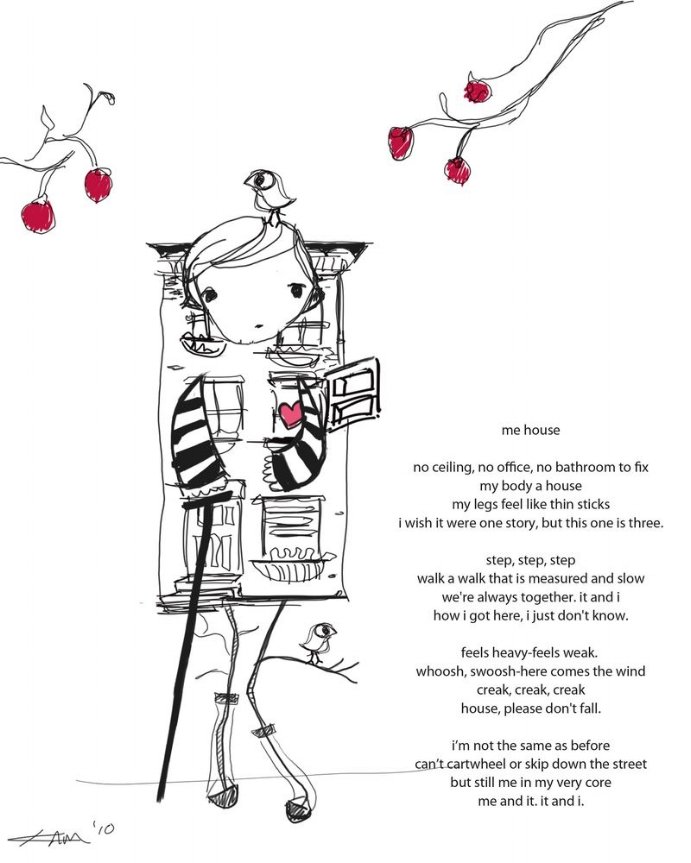

I like who I am, a hodgepodge of experiences I’ve collected along the way. I am not just American, Korean, disabled, an artist. I crave experiences and views that are truly different than my own. That is who I am. My background as someone who never quite fit in, I suspect, helped inform this perspective.

Of course, I still wonder about my past and have become increasingly interested in my biological family. I do not fantasize about my birth family and how my life could have been (better), but I do wonder about my biological mother’s story, her life and what events caused me to come about. Since childhood, I have had recurring dreams of this past. I wondered if she held me before she left and the thoughts that surged through her mind. I wonder about the story of her life.

My wrinkled tissue paper adoption records are all I have as proof that I was once a little girl in Korea. That I was once Kim Young-eun (Korean name given to me at birth) who loved dancing and singing “Goyohan Bam, Gorughan Bam” (Silent Night, Holy Night), hated naps, looked forward to the occasional cookie and TV time, and loved to be loved, even if I only allowed it at arm’s length.

I know many fellow adoptees who have struggled with identity or came from bad households, living a life of turmoil, loss, unrest, heartache, resentment and anger. Many have been left in the dark, lied to about their pasts or were victims of the system. I can’t speak for these adoptees because each experience is unique, but there is a common thread of something missing, a loss, this question of identity.

But, there is an identity seeker in all of us, orphan or not, and it is a journey that is never concluded. I think many of us search for the past to seek our future. I allow my past to be a part of who I am, without letting it dictate my present or future. I live with the philosophy of not allowing it to be a stumbling block.

To me, identity is like a Katamari ball that constantly rolls, absorbing every experience. No one experience is inferior to the other, and it is a constant adventure.

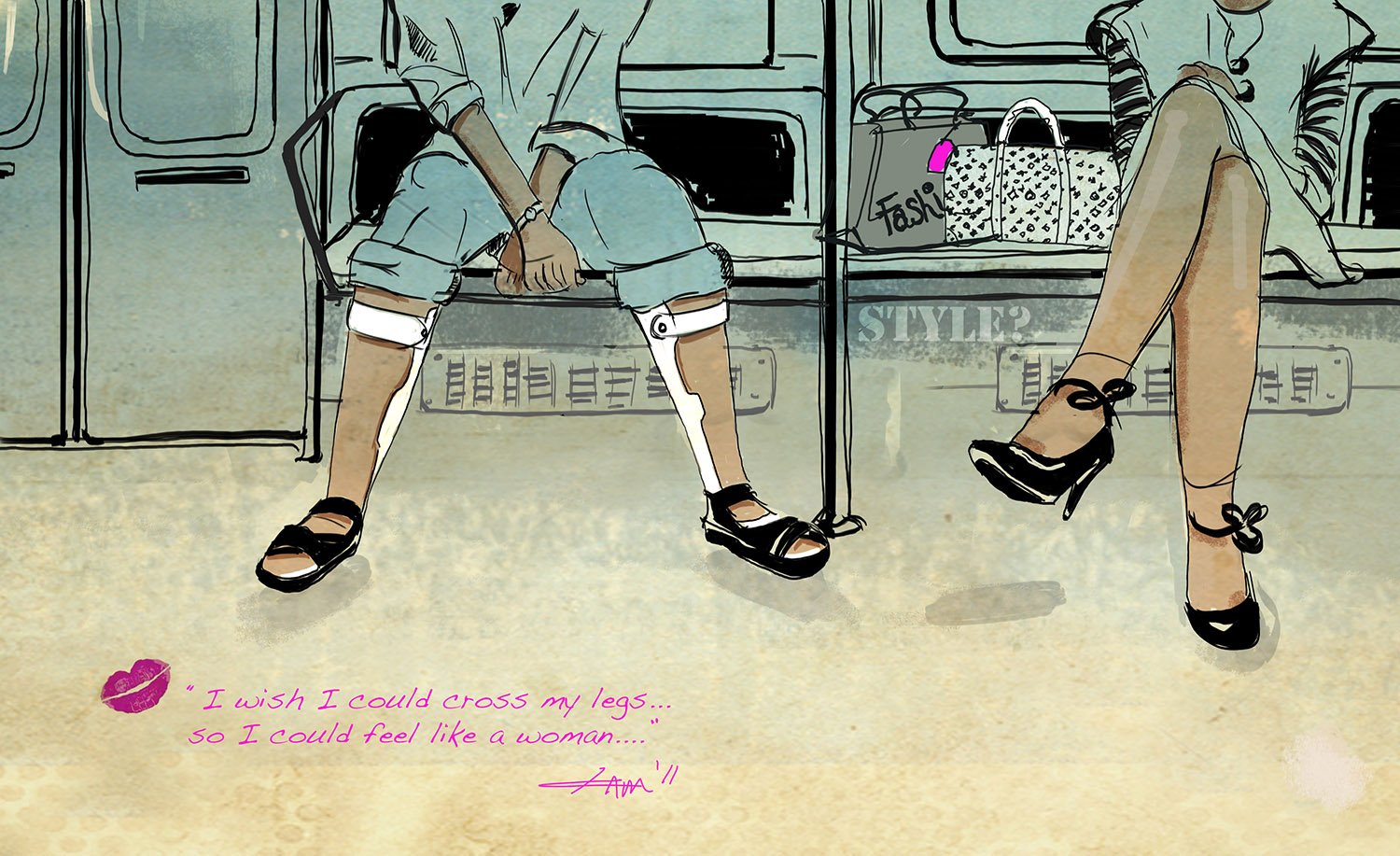

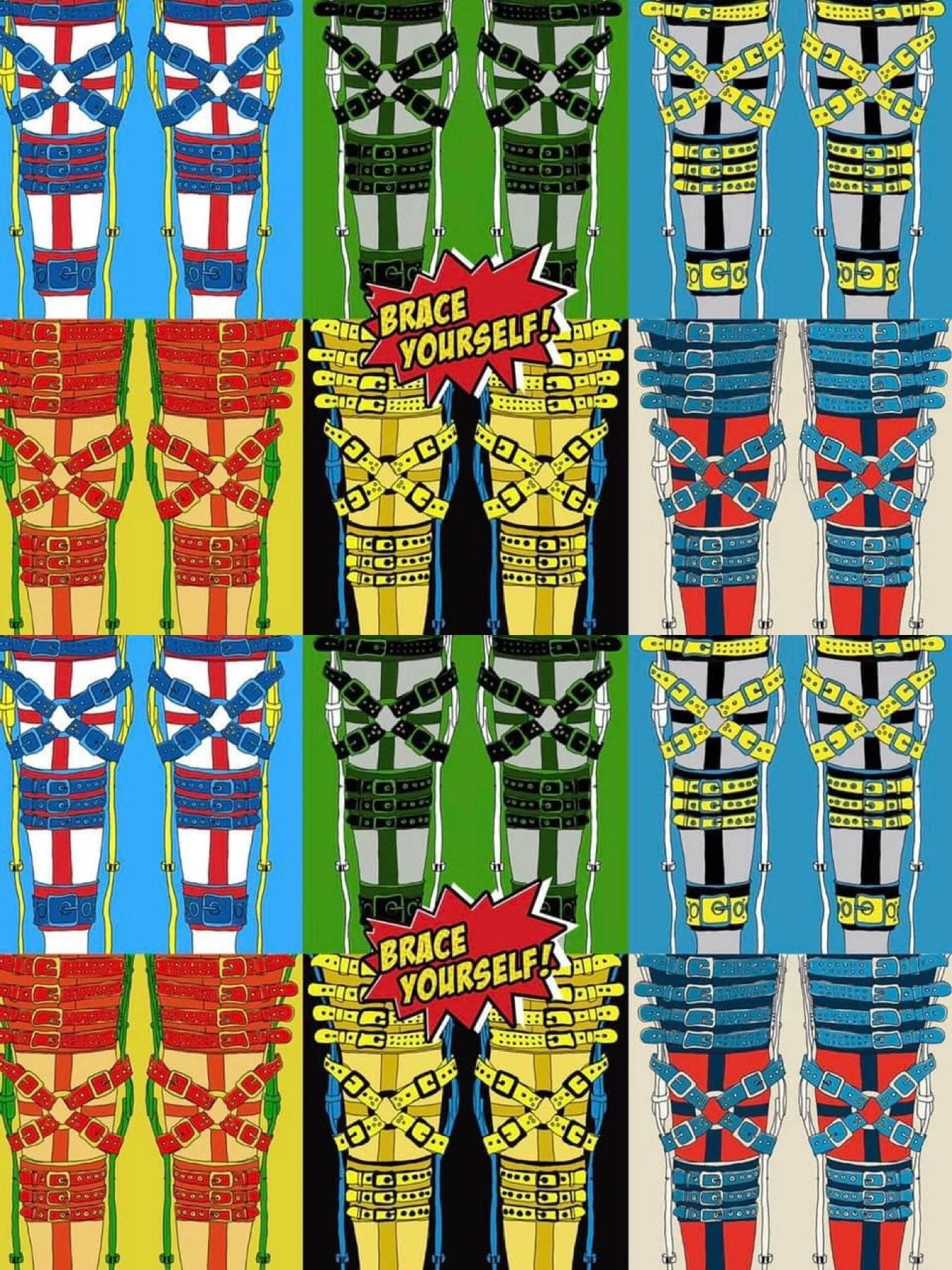

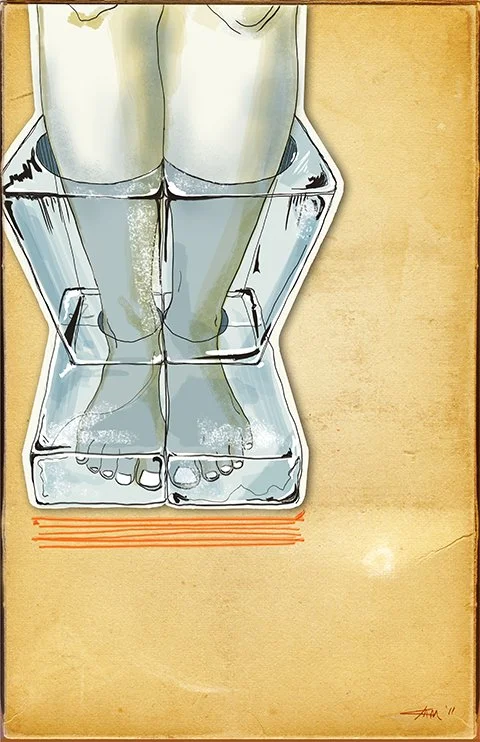

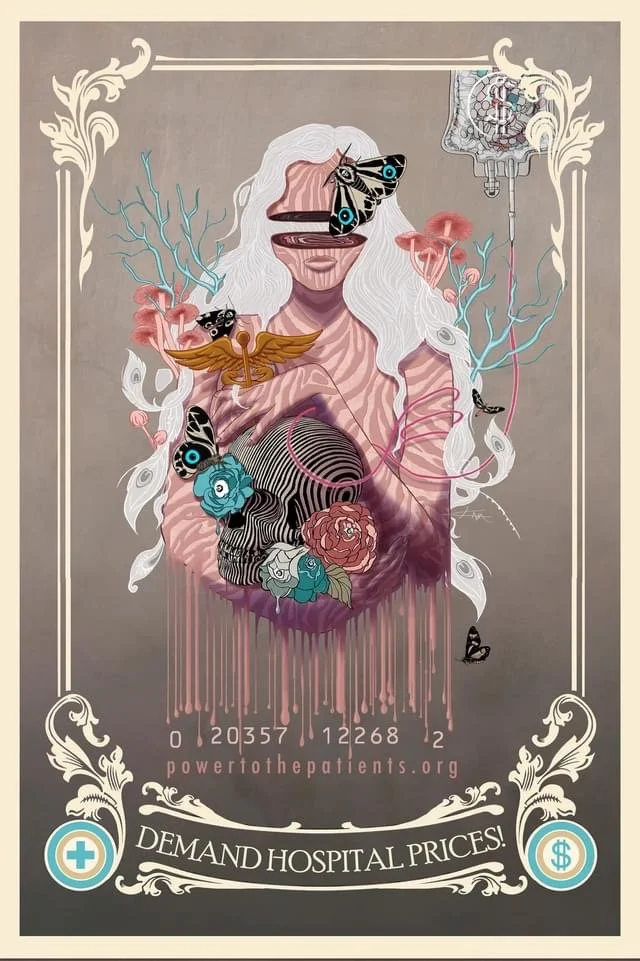

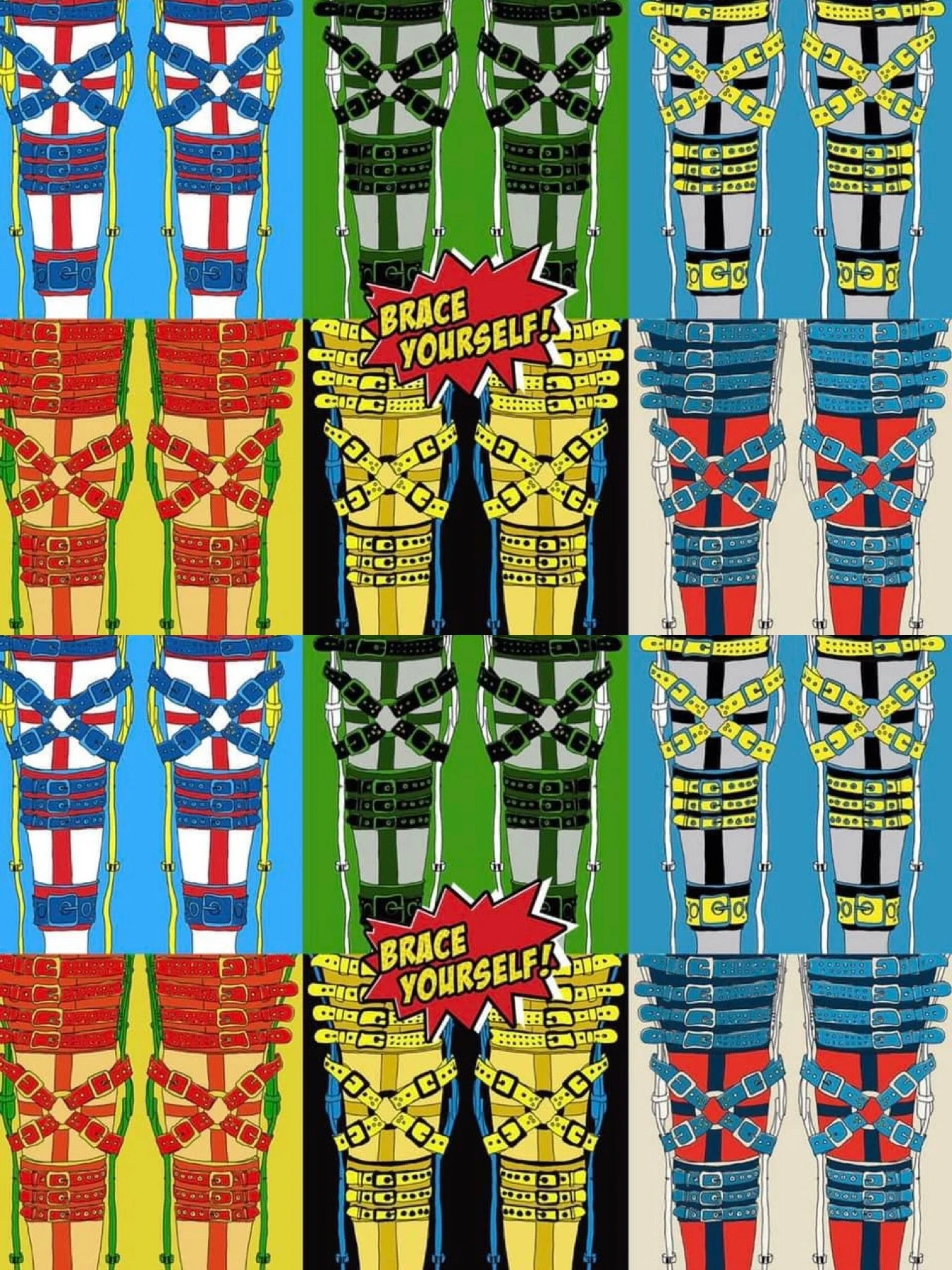

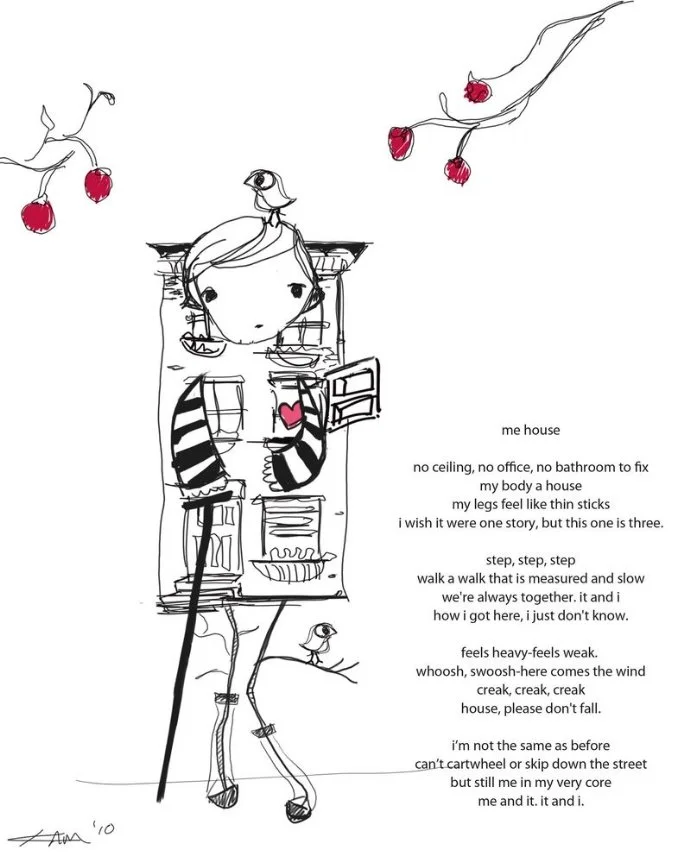

Epilogue: In 2007, I had DNA sequencing done and was given a definitive diagnosis of GNE Myopathy (back then called, Hereditary Inclusion Body Myopathy, HIBM), a very rare genetic, debilitating, degenerative muscle-wasting disorder. This diagnosis put an end to nine years of searching for what was causing my weakening body. Unexpectedly, it also acted as a biological microscope to a past I never met. My disease is genetic, and the mutated gene combination of my biological parents had been passed on to me.

I have had this disease since birth, but, unknown to science, the disease doesn’t begin to express itself until one’s early 20s. Despite never meeting my biological parents or knowing my history, a glimpse had now been given to me. My parents had become more tangible. They were written in my cells, and are having a profound influence on my life and my future. They are like shadows on the wall. And, in a way, this knowledge of my biological parents being carriers of this mutated gene that did not carry physical manifestations for them as it did for me brought about a great sense of humility, as well as a deeper connection to and interest in who they are.

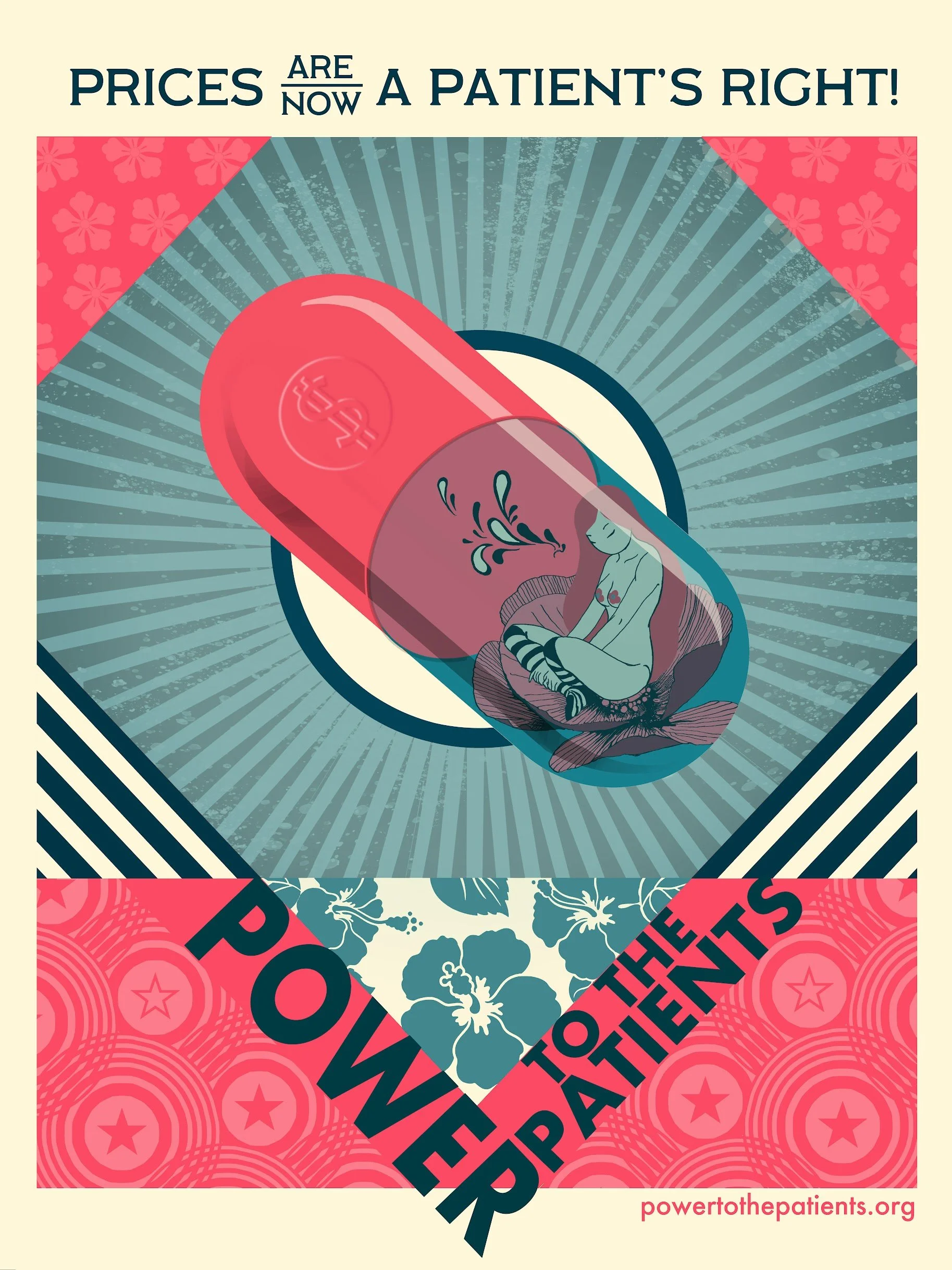

Follow Kam’s wheelchair travel, mini-memoirs, art, and disability and accessibility musings on Instagram at instagram.com/kamredlawsk.