It’s not uncommon for adoptees to wonder if their biological mother ever thinks of them...I know I have often. This mother spent 44 years searching for her daughter (Lauren) — the “girl with the flower shoes” — up until they were recently reunited. (video below)

After the Korean War to my birth time (50s - 80s) there was a major boom of overseas korean adoptions. Adoptions was a major money maker and helped bring Korea out of the war depression.

We, the lost children, were Korea’s most profitable export. We were the societal fallout post WWII era.

The dark side is many times children were either stolen from mothers or told their baby died, often by family members or strangers looking to profit from the international adoption boom, and these children were secretly put into adoption or abandoned at police stations.

The reasons were various but many times they were single mothers who were either forced to give up their baby or their child was taken because it was socially unacceptable to be a single mother. Another reason was because they were girl babies taken by husbands who would abandon or put them in orphanages because they weren’t a boy. Other reasons include being mixed race babies who were abandoned by their American GI (military) father. Many times these men had wives and children of their own in America.

Thus we were nationally unwanted children.

Today, single mothers are still looked down upon in Korea. It’s also still taboo for Koreans to adopt their own as it messes with “one blood”; a myth of racial purity. Although this is changing...slowly.

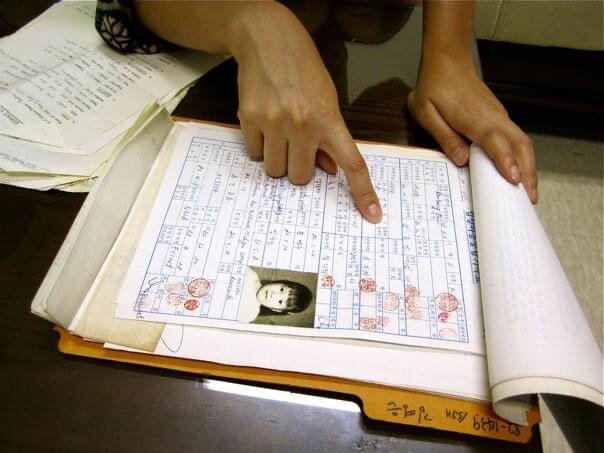

Keeping accurate and transparent records was also not a priority back then. Even further severe, records were sometimes changed or children were swapped and sent overseas under another child’s identity. I read these kinds of systemic adoption stories all the time. A lot of child trafficking happens this way, not just in Korea.

War is most prolific on women and children, moreover countries of color, which is why I’m so against wars and those who dishonestly perpetrate them.

We are usually seen as romantically “saved” by the West, while undergoing mass assimilation and stripped of cultural identity, but the story is so much more complex.

I think Korea’s adoption history is a microcosm and shows the effects of war, societal prejudices, stigmas and other social aspects that trickle into national and worldwide social crises. Like being a single mother. Why is this even a stigma anymore? What do these close-minded biases and fears accomplish? Isn’t the true meaning of life about happiness, love and giving love?

When cries are ignored, and we push our own views and value system onto others, like being anti-gay or anti-single mothers, humans are the collateral damage. When our concerns are more for individualism over those who suffer and are exploited, it reverberates through generations.

In the last few years, with the help of genetic testing spearheaded by fellow Korean Adoptees (KADs) who run family connection social media groups I follow, a generation of Korean adoptees have been returning to Korea to hunt for a past and family we were never privileged to know.

I support adoption but like most issues there is a lot of shaded grey that shadows lies, deception, injustice, the disenfranchised, heartbreaks, detachments, and for some, sexual and physical abuse committed by adoptive families, foster parents and/or orphanages — leading to suicides and lifelong scars.

For both sides, adoption can mean loss.

Not to paint a sad picture or discourage adoption, I’m for it. The alternative is millions of orphans coming of age and put onto the streets because the orphanage can no longer house them.

Jason (my husband) and I are fairly adjusted and fortunate to have had good adoptee experiences with good families, but there is a history there; like a shadowy figure on the wall that does not leave many of us.

It is not always the romantic picture of children being “saved”. There is still trauma and healing is required for most.

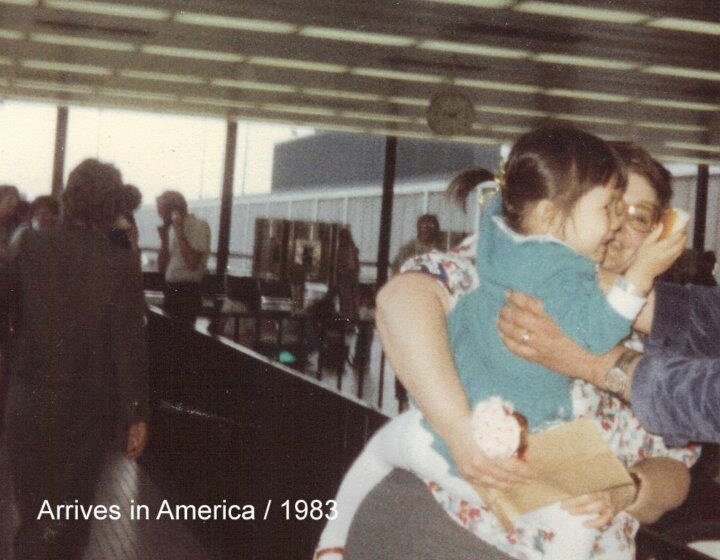

I remember my mother telling me I cried for my “umma” (Korean for “mother”) for 3 months when I first came to America. She also said I was very afraid of baths and hot water and noticed I had boils on my body, as if I had been burned.

That kind of trauma never leaves you.

I’m lucky to be self-adjusted and have handled my adoptee journey pretty well, but this is not the case for many and I do not speak for all adoptee experiences. Every adoptee reacts to their journey differently; many times because their experience was sprinkled with more tragic elements beyond being abandoned and lack of identity.

I think many adoptive parents, out of lack of knowledge and education, assimilate adoptees into white culture and we are unwittingly forced to forget our past and culture. And then when we reach of age, we begin searching for ourselves, realizing our life did not actually begin when we were adopted. We had a past that dwells in our subconscious.

This is not malice and parents do their best, but times have changed.

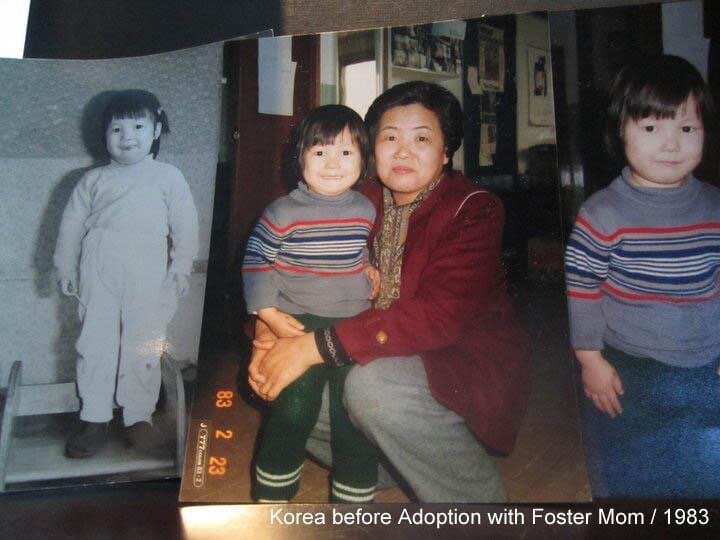

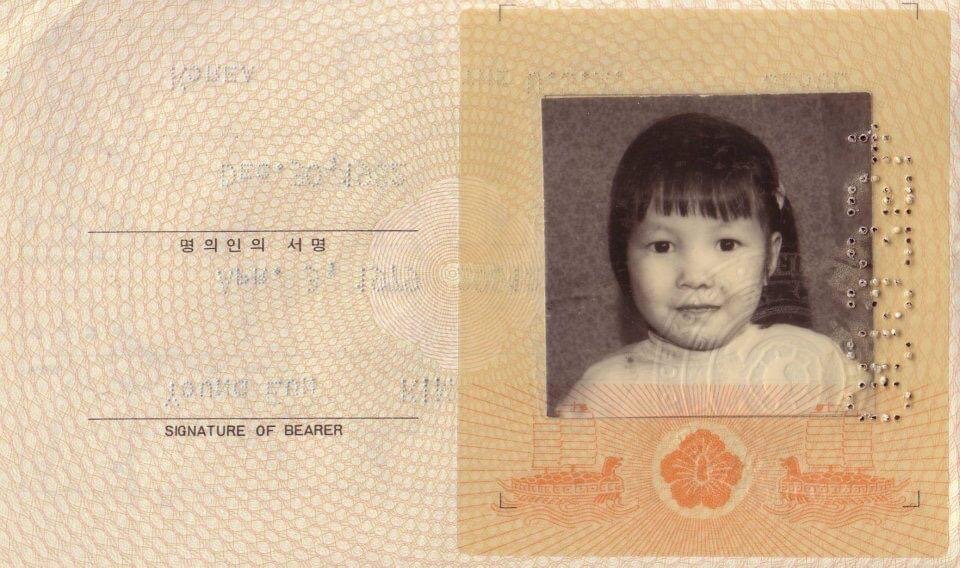

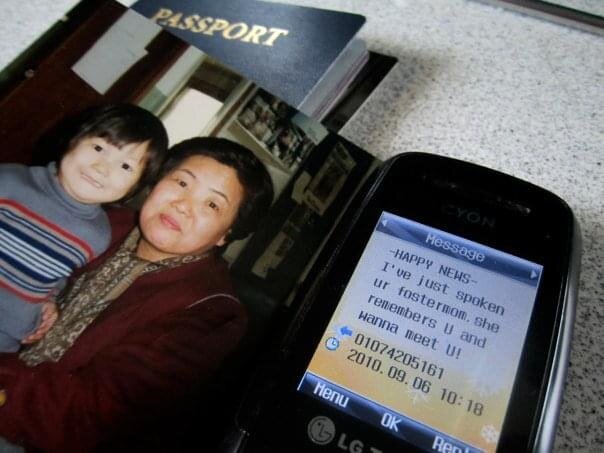

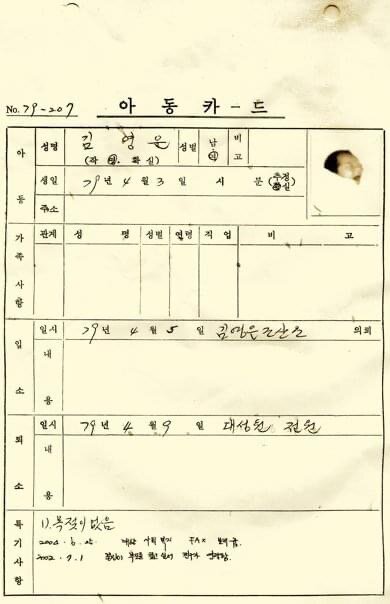

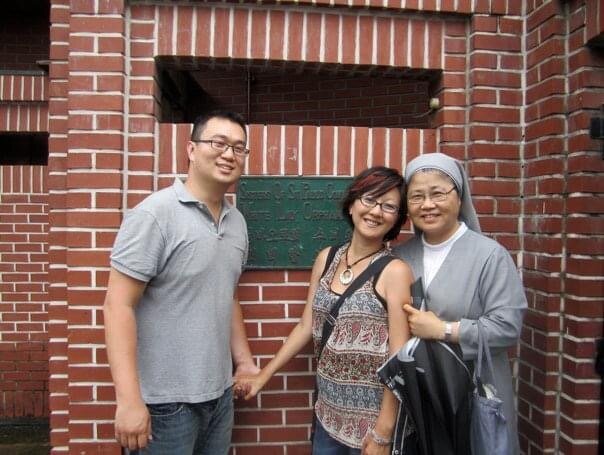

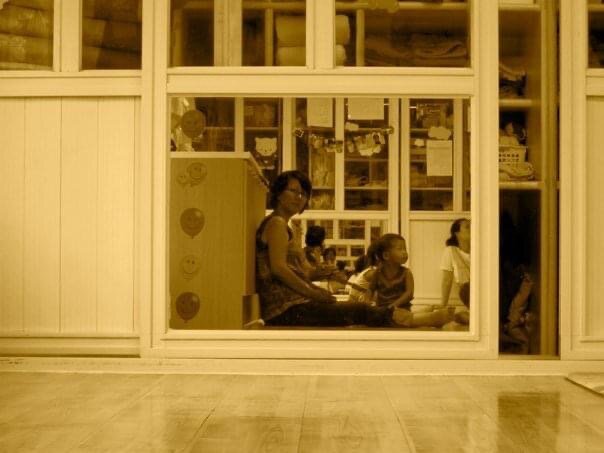

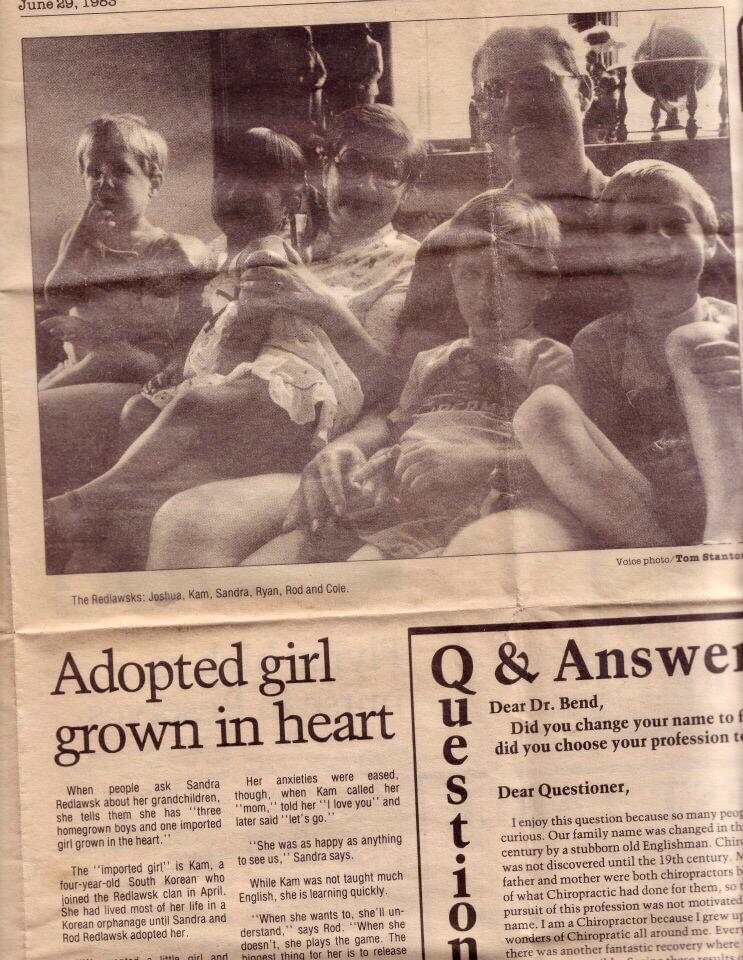

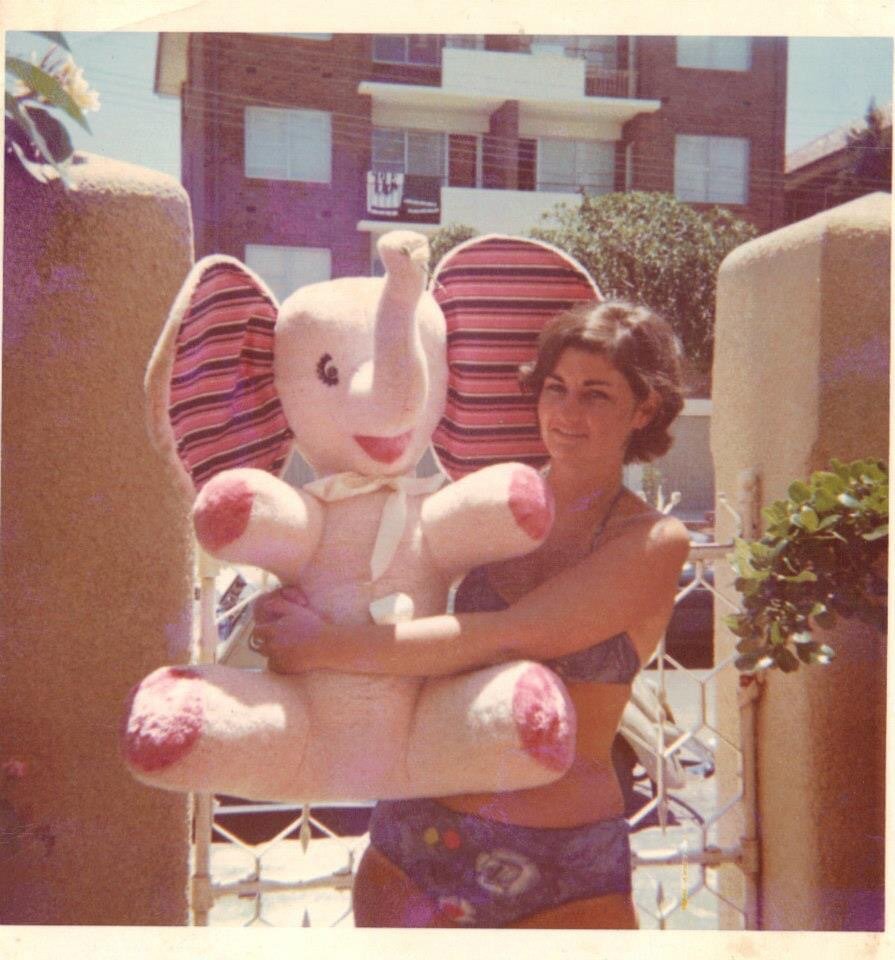

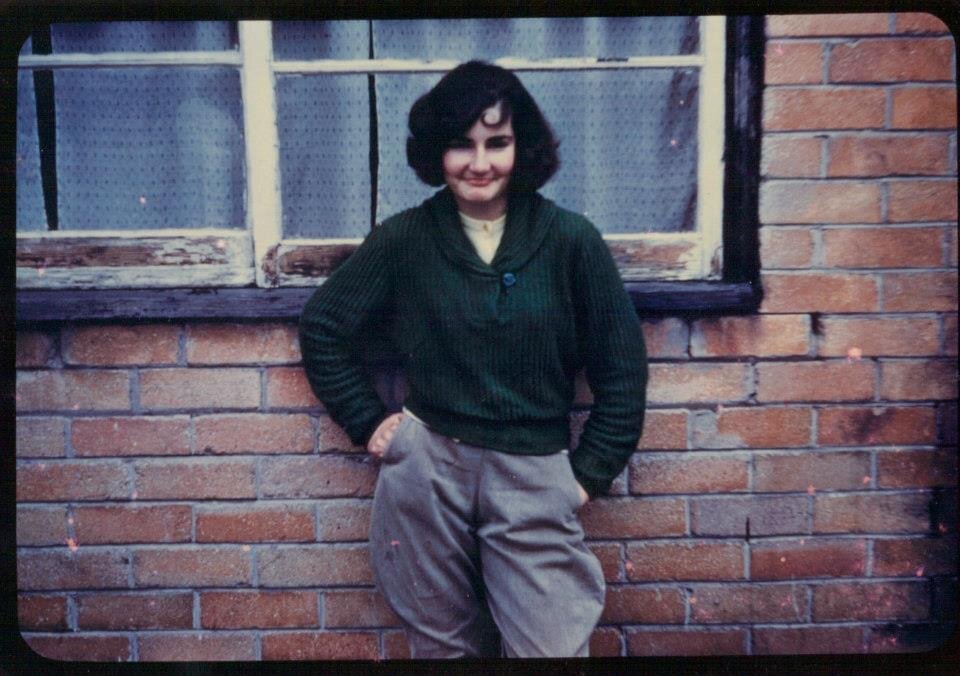

Above are some of pictures of me before my life in America, and my travels back to my adoption agency, two orphanages I lived in and meeting my foster mother in 2010. During this time I was known as “Young-eun, Kim” and not ”Kam”.

My husband and I are both Korean Adoptees. This (us both being adoptees) happened accidentally, not intentionally.

I was born in Daegu, Korea in 1979 and bounced around from maternity clinic to orphanages to foster parent.

My final destination was Michigan.

As my 2017 LA Times feature said about my story: “Redlawsk would never know who handed down those fateful genes. She had been hours old when left at a maternity clinic in Daegu, South Korea. Born with a cleft palate, she battled measles, chicken pox and a deadly virus all within the first months of her life.”

I recently found out by a fellow Korean adoptee that Daegu, my birth town, was the epicenter of abducted children. Daegu is the second or third largest city next to Seoul and very poor back then. In poor areas all the dark sides of the system I mentioned above was especially prevalent.

Mothers were often threatened with public humiliation and/or legal action from orphanages that stalked them in birthing centers. And if mothers couldn’t pay their hospital bill, their child could be taken. Because of this, police have special officers dedicated to these abduction cases in Daegu.

Learning this has broadened the potential script of how I came into this world. My paperwork says my biological mother gave me up at birth. Without signing any papers, she allegedly slipped out like a phantom immediately after I was born. The maternity clinic named me and my paperwork is sparse of any names or real details.

But now I wonder. Maybe I wasn’t given up at birth. Perhaps, I was taken or my mother was told I died.

I may never know.

My only connection to my past is my genes. My face, my eyes and this genetic muscle-wasting disease I’ve had for twenty years belongs to my biological family.

One day I hope to find them.

I think after losing my own (adoptive) mother three and a half years ago, and knowing I will never have children of my own — a personal and heart-breaking decision I made because of my progressive muscle disease — the curiosity to see something familiar has intensified.

(Note: I hate saying “adoptive” because I view my mother as my real mother but mentioning for clarity sake. Also, people with disabilities can and are parents and every bit as good of parents as “able bodied”. Not having children for myself is a personal decision.)

One day I hope to see the eyes who gave me my eyes. This is a privilege most take for granted. And, who knows, maybe she is looking for me, too.

I’ve tried searching for my biological past on a few occasions, but no way have I exhausted all the possible search avenues yet. I need to stop using lack of time as an excuse and really dive into genetic cataloguing. I’ve done 23&Me genetic test, which told me I was also part Japanese, but this is just the beginning steps. I need to upload my information to all the available genetic banks and take additional genetic tests, something I’ve recently ordered.

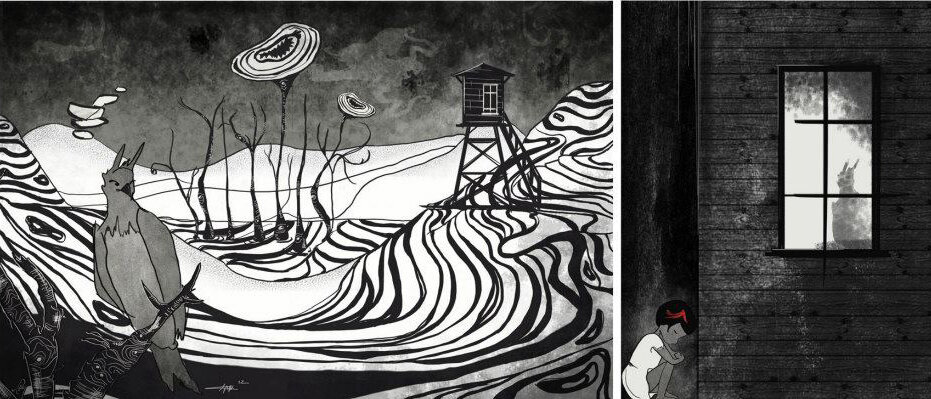

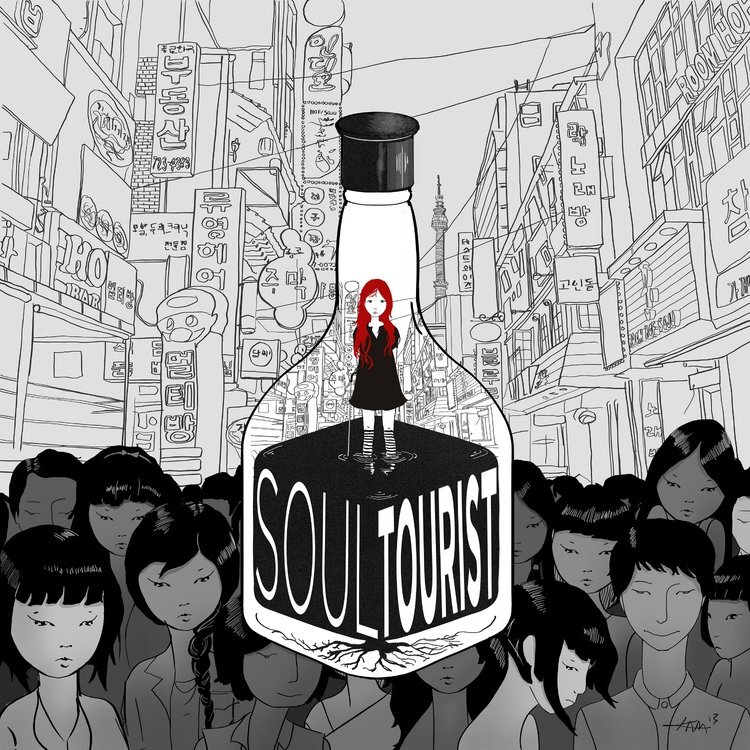

Through the years I’ve done a few illustrations and written column pieces inspired by my adoption but rarely talk about this aspect of my life, not because I don’t want to but because I have little time due to my disability advocacy. But I would like to share more about my adoptee experiences in the future.

I’ve been back to Korea twice: once in college by myself and the other time when I took my husband to visit his homeland for the first time.

On my second trip back in 2010 I got to visit my orphanage(s) and met my foster mother, Kyung-Sook. Despite 40 years of fostering tens of dozens of children she remembered me fondly in a way that only a mother could. That was an amazing experience I’ll never forget. I’ve been meaning to do a video of this travel back-in-time from 2010 and share this moment, but time has escaped me as it’s already 2020. I also didn’t really begin documenting my travels until 2011 so my footage of traveling back to my orphanage is sparse, which I regret.

But I’m putting it out there for accountability’s sake. This year I will find the time to do the steps I need to broaden my genetic search.

Not all of us have the same traditional paths in becoming mothers or finally receiving a mother.

My mother was from Australia who had three natural born sons and wanted a daughter, so she adopted me. My father and uncle named me after a figure skater and shifted my Korean name “Young-Eun” to my middle name, an act I’ve always been thankful for.

A korean friend told me my name translates to “Silver Bell” but who knows.

My mother had her own past and did her best despite a tumultuous childhood and an off-beaten example for a mother. My mother had an Aussie accent that all my friends loved, quirky humor and laughed at her own jokes before she could get them out, something Jason says I do all the time. She taught me how to cook and how to be giving as a language of love. She was a good mother. I thank her for giving me love and a family. I miss her dearly.

With no nucleus family to call my own, and no mother, I sometimes feel....displaced…like I have no home. After my mother died three and a half years ago, I wrote a letter to her and read it at her memorial. I shared that her passing oddly made me feel like an orphan all over again.

My life is anything but traditional and sometimes that can be painful — to not have what everyone else has — but in other ways it is special because I’m so unique. I’ve been able to experience so many perspectives not usually found on a typical path.

From being an adoptee, to a person with a disability, to becoming a self-taught illustrator and writer that doesn’t have the traditional milestones of having a family, to being a public advocate, plus other non mainstream aspects of my life experiences — I’ve been able to experience a spectrum of the human experience. So I have that.

Modern Love: families take on many shapes and sizes.

In the end a parent should love but not all of us are privileged to have (loving) parents. But we do our best to find that support and love wherever or in whomever is willing to give it to us, and that is all that is important.

Finding love, giving love in whatever way we can.

Our parents are not perfect and I think we realize how hard it is when we become parents and see how unfounded all our expectations of them were when we young. I’m speculating because of course I’m not a parent.

Try not to live by too many expectations, it destroys the experience of now and recognizing what we do have. Have a direction, a purpose and passion and the rest will fall in line.

Happy Mother’s Day to mothers of all forms: to the mothers who have lost children and the children who have lost their mothers, to those expecting or celebrating their first Mother’s Day, to foster mothers and even those desperately trying to become mothers, and everyone in between. But especially to those who have traveled non traditional paths to motherhood and the motherless who gained mothers in unique ways. This one is for you ❤️

Follow my wheelchair travels, art and musings @ Instagram.com/kamredlawsk

Extra, Extra!

Here are some of my illustrations and column snippets I’ve written in the past inspired by my adoption:

Soul Tourist: Infinite Seeker

The Gift: Perpetual State of Searching

What I wrote in my journal in 2010 when I visited my birth town, orphanages and met my foster mother:

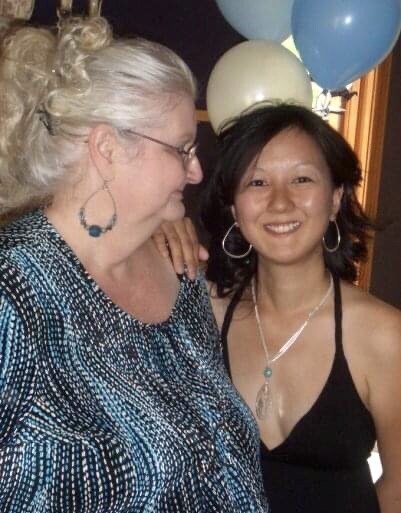

” Foster Mom Kyung Sook and I (Young-eun).

A few days ago my foster mom had pulled out old pictures of me and wondered how I was doing. She then received a call from my social worker who told her that I was in town.

We met and as soon as she walked in she immediately recognized me and said I look exactly the same while tightly cupping my face — much like a mother recognizing her own child.

“Exactly the same", she kept saying. She couldn't stop hugging me and looking at my face. She told me long ago I was her shadow and she could see after living in an orphanage for so long, I had never known what it was like to have a family. Her own children were grown so it was just her, me and a tiny foster baby with her back in '83.

She said I was a very quiet girl who loved to sing. Though I was her devoted little shadow she waited patiently for me to open up emotionally and it took me a month to finally call her "Umma" (mom in korean), something she had been waiting for.

That day I tugged on her shirt while she was cooking, looked up at her face and called her "umma" for the first time.

The day I left for the America to meet my new family she cried while taking me to the airport. I guess I cried as well and didn't want to go. Eventually, she had to hide in the airport because I was crying so much and officials needed to take me to board the plane.

She then watched me leave until my plane became a speck in the sky and went back to an empty home missing me.

She is now 75 years old but seemed so spry, with it and very warm. She had fostered children for 40 years and admittedly didn’t remember the countless children she fostered but she remembered me fondly.

I noticed she seemed unusually open. For example, when she heard about my muscle condition she said she that she was sorry and that she could remember me running as a child, but she didn't act like it was a tragedy. I hate to say it but many Koreans don't view disabilities kindly and they pity you, but she seemed unphased by it. Which was really special and progressive.

I get so many stares here in Korea and disability is not as accepted or understood. Many Koreans don't see actual disabled people because those that are disabled stay in their house and don't come out due to society’s prejudices. But, she looked at me with warmth and said she could clearly see I grew up to be someone and that she was proud of me. She wished that my birth mother could be found, so that she could see how I have grown and how wonderful I was (her words--not mine 😉)

In some ways it is probably more meaningful to meet her than my biological mother because she is the only one who knew and loved me in Korea, and I am most thankful to have met the one who loved me when I was so small.

In one of the pictures I was laughing so hard, because she gave me skin care products as a gift. I laughed, because Koreans, in their quest for eternal youth are REALLY into face skin care. My friend JUST got done telling me this fact before I met with my foster mom, haha, I am NOT into skin care 😉 but totally should be.

More stories to come on my blog when I return.”

I never ended up finding the time to blog this travel experience to my past…but one day I will.